Performance estimates analysis

Analysis of Performance Estimates for Heat Technologies 2016

Publication Date: May 2017

Contents

1 – introduction

2 – the new MCS standard

3 – results from new analysis – estimates in 2016

4 – performance and financial forecasts

5 – problem marketing

6 – conclusion

Section 1: Introduction

In March 2016 the Renewable Energy Consumer Code (RECC) published a report on the compliance of performance estimates given to domestic consumers for the three Microgeneration Certification Scheme (MCS) heat technologies – heat pumps, biomass and solar thermal. The analysis measured the performance estimates against industry standards as defined by MCS and by RECC.

That evidence from RECC’s research found that many estimates presented confusing and sometimes misleading information about both potential performance and financial savings/income.

The RECC research involved:

- a review of the obligations on consumer performance information within the MCS standards MIS 3001, MIS 3004 and MIS 3005;

- the development of three technology-specific compliance tools to assess performance estimates consistently;

- an analysis of nearly 50 actual performance estimates given to consumers by installers collected during routine RECC audits and other compliance monitoring activities;

- a review of research evidence available on actual in-situ performance; and,

- the development of recommendations.

This paper updates the above research for heat pumps only and places a new analysis within the context of changes to the MCS Heat Pumps standard agreed in January 2017 (Section 2 below).

In light of the recent revision of the MCS standard, and noted by the MCS Heat Pumps Technical Working Group, RECC will undertake further monitoring of installer practice at the pre-contractual stage. RECC members must comply with relevant MCS Standards related to performance estimates.

Further research on the pre-contractual information given to consumers will include:

- further analysis of actual performance estimates obtained at audit;

- and examination of the financial claims made by the installers in all material given to consumers as part of the sales process;

- a marketing survey; and,

- a check on which companies are using ‘off-premises’ contracts (home selling) and whether this business model is linked to non-compliance at the pre-contract and contract agreement stages.

Input from other stakeholders on RECC’s monitoring is welcome.

Section 2: The MCS Context

The new version of the MIS 3005 is expected to become compulsory in October 2017 . The new standard includes a range of technical, process and administrative changes that will impact on consumer protection. The following are the most significant.

Compulsory Performance Estimate

RECC has argued for the introduction of a standard compulsory template for heat pump performance estimates since our original research on performance information was published in 2016. The new compulsory template is in the form of an Excel file that automatically calculates the running costs, savings and RHI income depending on a range of values entered by the installer. The energy demand is obtained from the consumer’s EPC. Installers will have to give this completed template to consumers before contract agreement.

Contract agreement before survey

The new version of the standard no longer requires installers to carry out a full room-by-room heat loss assessment at the pre-contract stage. Contract agreements that change significantly after the home survey will be subject to a variation of contract. As contracts can now be agreed before the full technical survey is carried out, RECC predicts that some installers will be more likely to use sales agents for home selling. Home selling was, and still is, widely used in the Solar PV market and RECC is concerned that this may lead to more non-compliant sales practice.

The compulsory use of SCOP data

The calculations in the new performance estimate template are based on Seasonal Coefficient of Performance (SCOP) values obtained from the MCS website. Installers then paste the SCOP data into the new compulsory performance estimate spreadsheet and. The SCOP value in the spreadsheet is used to calculate the heat pump efficiency and the expected RHI. In response to widespread concern about the use of SCOP values to estimate in-situ performance, the new estimate template includes a warning/disclaimer regarding the accuracy of the performance information based on SCOP.

Alternative estimates must now always carry warnings

Heat pump installers often give consumers additional or ‘alternative’ performance estimates. Frequently, these ‘alternative’ estimates do not reflect the values calculated using the MCS methodology and can exaggerate performance claims. The new MCS standard requires all alternative estimates to carry a warning that the figures should be treated with caution.

Section 3: Results from new analysis

This year our analysis has included 12 performance estimates from a wide range of companies from the across the UK. The estimates were assessed using the RECC performance information compliance tool as a consistent check. The procedure used by RECC to select companies for audits and spot checks is risk-based which means that the companies included in this report are not a random sample of RECC members. The sample does, however, reflect the experience of a significant proportion of domestic customers because the companies selected for audit tend to be larger.

Four relatively large companies are included in this analysis (Table 1 below) – one of those companies is responsible for PE4 and 5. Performance estimates 10, 11 and 12 were issued by a different large company in 2016 when it deployed home selling. That same company then radically changed its business model and PE’s 8 and 9 are more recent.

It is also important to note that each proposal analysed is likely to reflect typical practice for that whole company at the time. The performance estimates described in this report therefore reflect the business models deployed by the installers and the broad experience of the customers during that period.

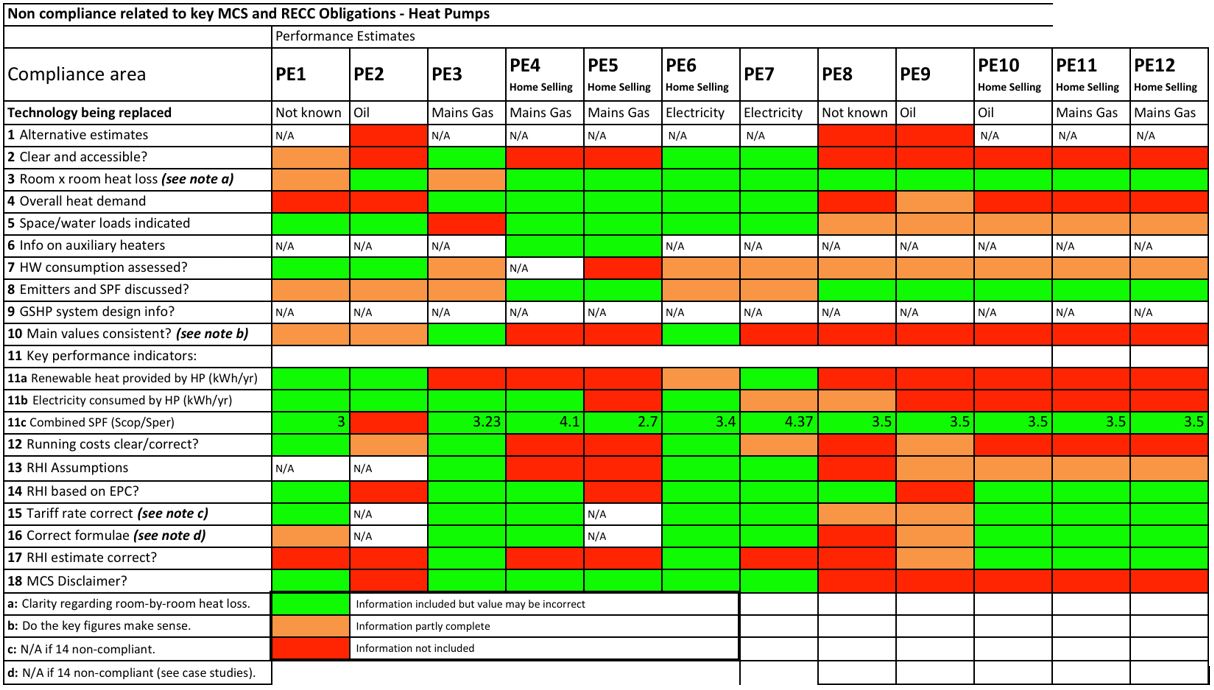

Compliance with the main MCS and RECC requirements is summarized in Table 1. Green indicates compliant practice; red indicates non-compliance and orange partial compliance (or compliance was not clear).

Table 1. Analysis of Heat Pump Performance Estimates - 2017.

The main findings of this analysis are summarised below.

- Seven of the estimates gave no combined figure for total heat demand or this total figure was unclear (three of the seven companies).

- The main performance values were reasonably consistent for four companies (four estimates) (this is a measure of consistency between the overall demand, the SCOP, the electricity use by the heat pump and the renewable heat delivered). The figures were unreliable in all of the other estimates (three companies).

- Eight of the estimates were provided by three companies as part of a contract agreed ‘off-premises’. IE – Home Selling. Seven of those were very non-compliant.

- The main values were significantly misleading in several (see below).

- Installers are required to give consumers several key values but three are critical:

- overall demand;

- electricity consumed by heat pump; and,

- SCOP.

Only four estimates included all of those values (four companies).

- Two of the 12 estimates that gave RHI income predictions wrongly based the figures on their own demand assessment rather than the EPC.

- Only five of the 12 estimates calculated the RHI income correctly (three companies).

- The information about running costs was clear in only three estimates, unclear in two and misleading in six (two companies).

- All three estimates that included ‘alternative estimates’ (using an alternative methodology) were presented in a non-compliant way. All three were misleading.

- Only four of the estimates were reasonably clear and accessible.

- Six did not include the compulsory MCS disclaimer (two companies).

Section 4: Performance and financial forecasts

Performance

Table 1 indicates the various SCOPs predicted by the installers (compliance area 11c). Most predicted performance at 3.5 or above although one company was incorrectly using a SCOP at 3.5 as a default (for all installs). Two other estimates included predictions that were higher than SCOP 4.

Financial performance – all examples below assume the predicted SCOP performance will accurately reflect in-situ performance

Five estimates were for systems that would replace mains gas. Although the RHI is eligible for systems that do replace gas, BEIS makes it clear that the RHI is primarily targeted at homes that are off the gas grid. One example of marginal benefit relates to Performance Estimate 3:

Performance Estimate 3

- PE 3 is dated December 2016 and gives mains gas heating cost of £758.40 for a company estimate of 14806kWh heating demand.

- The company estimated the heat pump running cost to be £527.16 assuming a SCOP of 3.23 (11.5p/kWh).

- The annual energy savings are quoted as £231.24.

- The company estimated a total RHI income over 7 years to be £9205.

- Incorporating the RHI income and installation cost of £14,000, the ‘payback’ calculation is given as 20.73 years.

The company’s current gas heating cost assumes a unit rate of 5.12p/kWh.

A lower unit rate of 4p/kWh would give current annual costs of £592 and the heat pump would give an annual saving of £65.

- Company’s quoted energy saving p/a: £231.24

- Company’s predicted payback period: 20.73 years

- Energy saving based on 4p/kWh: £65 pa

- Payback based on 4p/kWh: 60 years

Misleading information is given in some of the other estimates for mains gas substitution.

Performance Estimate 4

- PE 4 is dated December April 2016. It is for a hybrid heat pump providing 76% of space heating only and no hot water. The company’s estimate of total heat demand is 20749kWh.

- The consumer’s current heating cost per year is given as £829 which is a unit cost of 4p/kWh.

- The company estimate of the heat pump running cost would be £435 based on a SCOP of 4.1 and 12.8p/kWh

- The annual savings are given as £394 per year

- The RHI income is given as £781 per year and the payback period is calculated as 17 years on an installation cost of £12450.

The benefits are overstated.

Firstly, the consumer’s current fuel costs are based on 20749kWh when the heat pump running cost is based on 76% of the EPC demand figure of 18363kWh (energy required to run pump = 3395kWh).

Secondly, the £435 ‘running costs’ is only the cost of running the pump and fails to include £272 additional costs (providing heating not provided by HP). The actual total run cost would be £707. Leaving an estimated annual fuel saving of less than £122 - not £394.

Thirdly – the total RHI income is given as £5467. Total annual savings £394. Total payback calculated as 17 years.

As actual fuel saving would be less than £122 the actual payback period would be over 50 years.

- Company’s payback period: 17 years

- Actual energy likely saving less than: £122 pa

- Actual payback likely to be more than: 50 years

PE 5 contained similar errors.

Performance Estimate 11

- PE 11 is dated December September 2016. The consumer’s DOB on the sales form indicates consumer is 74 years old.

- The company’s estimate of total heat demand is 21786 kWh and the consumer’s current heating cost per year is given as £950 - a unit cost of 4.3p/kWh.

- The company has given a ‘typical’ running cost for the heat pump (for the size of property) as £550 based on a SCOP of 3.5. Based on typical property.

- The saving is therefore given as £400pa.

- The total RHI benefit is given as £5110.

- Total contract price is £9000.

- Payback – about 10 years.

The company estimate of the HP running cost is not consistent with the estimated heat demand and SCOP of 3.5.

Based on the 21786kWh demand the energy for the pump would be 6224kWh costing £800 at around 13p/kWh (or £746.88 @ 12p/kWh)

The actual saving would be closer to £141 per annum

The company give the total RHI benefit as £5110, a total installation cost of £9000 and an annual saving of £400. This implies a payback period of less than 10 years.

- Payback period according to the company figures: about 10 years

- Actual energy likely saving less than: £141 pa (13p/kWh)

- Actual payback likely to be: 27 years (or approx. 20 years if HP cost @12p/kWh)

Heat pump replacement of other technologies.

Performance Estimate 10

- PE 10 was from the same company as PE11. Dated Sept 2016.

- The company’s estimate of total heat demand is 32262 kWh and the consumer’s current heating cost per year is given as £1000 on oil.A unit cost of just over 3p/kWh (which seems too low).

- The company has given a ‘typical’ running cost for the heat pump (for the size of property) as £650 based on a SCOP of 3.5.

- The saving is therefore given as £350 pa

- The total RHI benefit is given as £1600 x 7 = £11200

- Contract price of £12995

- Payback: 5 years

The company HP running cost is not consistent with the total heat demand and SCOP.

Based on the 32262kWh demand the energy for the pump would be 9217kWh costing £1198 at around 13p/kWh.

This indicates that the Heat Pump system would result in an increase in fuel costs of £198 pa based on customer current fuel costs of 3p/kWh.

These figures imply no payback.

If above is re-calculated based on a current fuel oil cost of 4p/kWh then existing spend would be: £1290. In that scenario the HP would offer an annual saving of £92 implying a payback of 19 years. (Or 10 years if based on HP costs of 12p/kWh)

Section 5: Results from marketing survey

Examples from limited marketing survey to identify potentially non-compliant marketing:

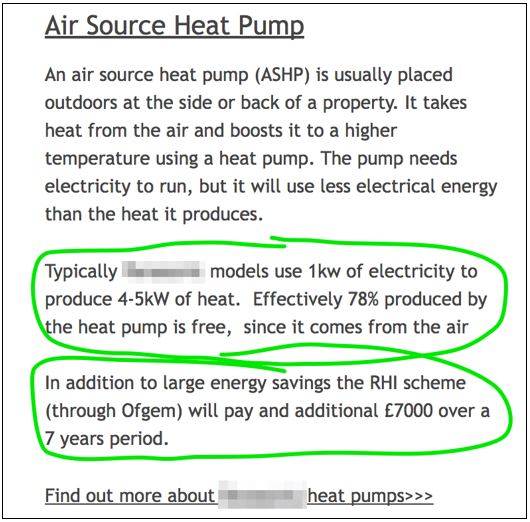

Example 1 (above) - Potentially misleading. The ad claims an efficiency of between 4-5kW of heat for every 1kW of electricity used and that this means that 78% of the energy output will be free. This claim is extremely misleading because that benefit will not be achieved in the vast majority of installations because the exact efficiency achieved in-situ depends on a range of factors specific to individual properties. The second claim that the annual income available is at least £1000 per annum is also incorrect because RHI income depends entirely on the EPC heat demand.

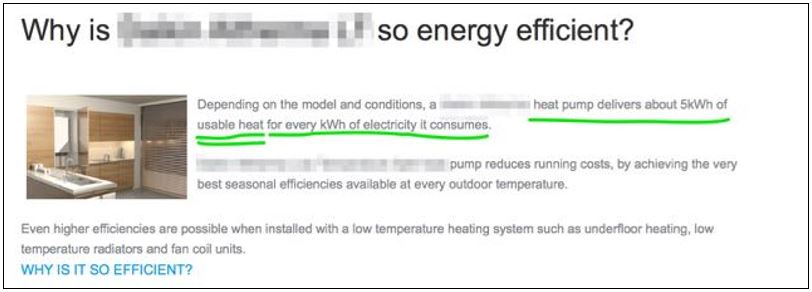

Example 2 - Potentially misleading. As above, the claim that this specific heat pump can deliver ‘about’ 5kWh of ‘usable heat’ for every kWh of electricity consumption is misleading.

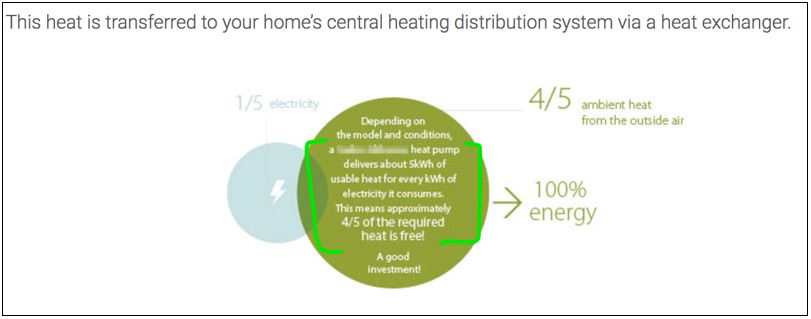

Example 3 - Misleading. This example is misleading because it asserts that heat pumps deliver ‘around’ 5kWh of ‘usable heat’ for every 1kWh of input. The statement ‘this means approximately 4/5 of the required heat is free!’ is not correct. The actual efficiency achieved will depend on the specifics of the property.

Example 4 - Misleading. As above, the actual ratio of heat produced versus electricity consumed depends on the property. The vast majority of installations do not achieve savings of 70% and, in many cases, savings on energy spend may be impossible without significant home improvement work.

Example 5 (above) - Misleading. The claim that a heat pump can mean a household can save up to 78% on ‘energy’ is not correct.

Example 6 (above) and 7 (below) – Potentially Misleading. These claim are potentially damaging because they directly target households on the gas grid. Most gas consumers are unlikely to see any significant benefit. The problems related to Example 7 (below) are compounded by the claim that heat pumps can convert 1kWh of input energy into an average of 3.8 kWh of heat. This implies that this is an average level of actual performance when the vast majority of installations will not achieve this in-situ.

Example 8 - Misleading. Again, this example implies that most – if not all – heat pump installations will achieve a specific level of performance. In this case a ‘seasonal efficiency’ of 550%. That level of performance will be impossible in almost all domestic scenarios.

Section 6: Conclusion

RECC’s first report on the performance information provided by MCS certified installers found that performance estimates offered to consumers were often inaccurate and were sometimes extremely misleading. The results from our 2017 analysis (described above) are similar. Only four of the 12 estimates examined were clear and accessible and only four include the three critical values consumers need to make an informed choice: the overall demand, the electricity consumed by the pump and the predicted SCOP.

This year we took the analysis a step further and scrutinised the financial forecasts provided. As Section 4 (above) indicates, some of those forecasts were extremely misleading. For example, several estimates indicate a ‘payback’ period of between 10 and 20 years. But the claims in those estimates were based on inaccurate or exaggerated performance values. Our calculations found that the accumulated savings and RHI income would not match the installation cost for many decades. In other words – the payback period would exceed the life of the heat pump.

Both RECC and the MCS standard require installers to provide consumers with accurate and compliant performance information. But RECC’s 2016 analysis of performance estimates across the three heat technologies indicated that the Certification Bodies responsible for MCS compliance were not assessing this performance information systematically.

The results from our 2017 assessment (above) reinforce that conclusion. The analyses carried out by RECC in 2016 and 2017 show that some companies do get it right. Those companies have clear processes for compliant practice and tend to use standard formatted quote documents that have clear fields for defined values. Some consumers are given excellent information and are able to make an informed choice. But, as RECC stated last year, many RECC member companies are frustrated to see other installers in the market clearly operating outside the MCS standards.

Markets improve when consumers can make informed choices. To that end, RECC is now working on strategies to improve installer practice on pre-contractual information. For example, we have demanded the introduction of standard Performance Estimate Templates (PET) across the heat technologies. Such a template is being made compulsory under the new MCS heat pumps standard finalised earlier this year and due for implementation before 2018. RECC is, however, concerned about the potential adverse impact of other changes included in the new standard. The new standard, for instance, will allow installers to agree contracts before the full technical survey is carried out. RECC predicts that this may result in more home selling. Home selling was, and still is, widely used in the Solar PV market and is linked to pressure selling tactics that are illegal.

While the introduction of the PET is welcomed by RECC, non-compliance may now shift to supporting advertising deployed by installers. RECC has highlighted non-compliant examples above and will continue to monitor the pre-contractual marketing and formal performance information offered to consumers under the new MCS standard for heat pumps.